In support of its mission to enhance the safety of critical infrastructure, Lloyd’s Register Foundation (LRF) sought to understand the relationship between safety in critical sectors and the psychological wellbeing of workers within them, resulting in this 2020 report.

Building on that work and with a focus on the maritime industry specifically, LRF has commissioned Nottingham Business School at Nottingham Trent University to conduct a rapid evidence assessment of existing industry and academic publications about interventions (i.e., initiatives) that support the wellbeing of seafarers. The work provides a baseline towards taking a systematic approach to understanding and sharing ‘what works’ for seafaring wellbeing. The full report from NTU is available here.

Why is this important?

The wellbeing of seafarers is a long-standing concern in the maritime sector. Traditionally the concern of maritime charities primarily, seafarer wellbeing is increasingly understood as a key influencer of the sector’s safety and sustainability, with every type of industry stakeholder - companies, regulators, states, etc. - having a role to play in its assurance. Wellbeing interventions are extremely varied and not always labeled as such, making it difficult to know which to adopt and how their effectiveness and scalability compares. This is particularly true of interventions relating to psychological wellbeing. While risks to seafarers’ wellbeing are high in general, risks to the psychological aspects of their wellbeing specifically are high compared to workers in other related sectors[1] and that this risk only increased with the challenges of COVID, especially the ‘crew-change crisis’.

What did we do?

A rapid evidence assessment (REA) involves identifying and pulling together the core publications around a given subject. Compared to techniques used for systematic reviews, REAs are conducted over shorter periods of time and involve making pragmatic decisions about what to include/exclude, based on criteria established at the start of the process, which often enables a broad and diverse range of publications to be identified. The criteria for this REA were designed in response to the following questions:

- What is the current state of the field (i.e. what are the current studies that link directly to this theme and what is the nature of the initiatives studied and the methods used)?

- Are there any common/general themes being explored within the evidence base?

- What are the current gaps and challenges; what has been identified or recommended as research priorities?

The REA, which in this case was limited to English-language, identified 691 publications as of interest, which was reduced to a final selection of 183. The publications cover highly varied approaches and initiatives concerning seafarers’ psychological wellbeing.

What have we learnt?

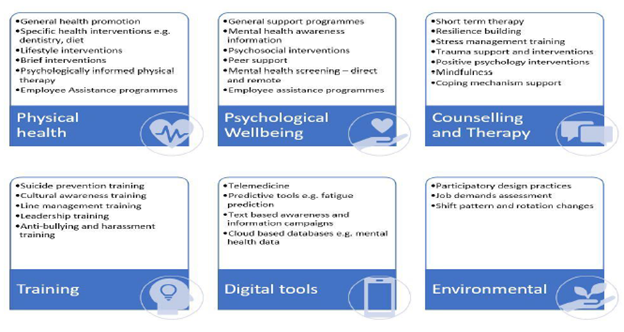

- The existing publications (listed in full in the report as an appendix) focus on six topic categories, as shown in the diagram below, with considerable diversity in the focus and nature of the interventions within each category.

- Psychological wellbeing was usually treated within a framework of stress, coping and resilience, and tended to focus on the individual seafarer, rather than relationships within the workplace or structural factors.

- There is no single approach to intervention that has gathered sufficient evidence for the identification of ‘active ingredients’ for supporting seafarer wellbeing.

- Where reported, the evaluations of the efficacy (i.e., whether it works) of interventions tend to demonstrate modest improvements, with the exception of physical health interventions, where there are some cases showing negative effects.

- Follow-up and long-term evaluations are very rare and there is little evidence of interventions being scaled-up or extended to other populations within the sector.

- There appears to be a preference for producing new and novel interventions rather than systematically refining existing programmes.

- Most studies are comparatively small (presumably as a result of small crew numbers and difficulties in access), with accompanying limitations in quality, such as an unrepresentative sample, lack of a control group, etc.

- There are very few ‘longitudinal’ studies (partly because the precarious and global nature of seafaring labour makes it very difficult to observe changes in the same individuals over a long period of time). Consequently, there is little data able to inform analysis of the long-term effects of working at sea.

What did the authors recommend?

The findings above clearly demonstrate gaps in topic coverage and in study types and methods, which if addressed (noting real and practical impediments) would provide a more comprehensive evidence base about how best to improve seafarer wellbeing in support of safety. However, for this or any evidence base to be useful, a single framework is needed to offer the possibility of unifying existing work and to provide a suitable benchmark for evaluation. Currently, this is lacking.

The authors also note that the diversity of the current evidence base may be a strength rather than a shortcoming because the potential to develop different methods for curating and analysing existing work could reveal novel opportunities for effective interventions that would not have been arrived at otherwise.

Additionally, while the REA found no one intervention with enough evidence to enable ‘active ingredients’ to be extracted and applied to improve seafarer wellbeing more broadly, it did find some evidence that seafarers themselves have clear preferences around interventions, while the publications also report that for many shore-based stakeholders in the industry, the importance of seafarer wellbeing remains underappreciated. As a result, the authors recommend a focus on ‘employee voice’ to manage differing expectations between stakeholders.

What are we going to do next?

LRF commissioned this REA to inform its planned ‘What Works Centre for Safety’ and specifically work within it aimed at establishing ‘what works’ for improving wellbeing of seafarers, in the service of safety at sea.

‘What works’ is a method that can be used to improve the impact that research findings have on people’s lives. It is based on the principle that good decision making is underpinned by good evidence, and if that evidence isn’t available, robust ways of generating that evidence should be established. What works recognises that research evidence on its own is not enough; you need to know how and why something works, for who, and finally, how to implement what is known.

Our anticipated ‘what works for seafarer wellbeing’ activity will build capacity and work closely with industry to fill the gaps identified in the REA, firmly based on industry need (including the perspective of serving seafarers) and crucially, to develop a unifying model for accessing, understanding and learning from existing and future work - made freely available to all.

For further information on the project, please get in touch via the form below.

[1] See Brown et al., 2020; Shah, 2021; Abila et al., 2022 - included in the REA report’s list of references.