Landmark SHE_SEES exhibition comes to Portsmouth

After its launch at last year’s London International Shipping Week, our SHE_SEES exhibition is opening at the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.

A roadmap for cleaning up potentially polluting wrecks.

This page is approximately a 22 minute read

This page was published on

A global, toxic legacy of shipwrecks containing vast quantities of oil, munitions, and other hazardous materials has been left by two World Wars. These wrecks are deteriorating towards instability, accelerated by climate impacts. Some are leaking and causing harm now.

Many of these wrecks lie close to vulnerable coastal communities, important fishing grounds, fragile marine ecosystems, marine protected areas and world heritage sites.

We are entering a decade of severely heightened risk of catastrophic damage caused by oil from these wrecks – damage to natural and cultural heritage that cannot be fully remedied. The harm to human wellbeing and the economic cost will also be enormous.

The time for concerted unified action is now. As we approach the 100th anniversary of World War II in 2039, we must commit to resolving this toxic legacy of conflict. The Malta Manifesto sets out the roadmap to do so.

The Malta Manifesto is an urgent call to action to marshal the resources and collective will to protect people and planet from catastrophic oil pollution.

Download The Malta Manifesto (PDF, 424.13KB)If you wish to use and reference The Malta Manifesto in your own work, please include the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.60743/dp2p-wa08

Example Citation in Harvard Style:

Lloyd's Register Foundation, The Ocean Foundation, and Waves Group Ltd, “Project Tangaroa: The Malta Manifesto,” Lloyd's Register Foundation, 2025. doi: 10.60743/DP2P-WA08.

The Malta Manifesto has been created to provide a roadmap for action on potentially polluting wrecks. But what are they, and why are they such a problem?

These ships contain different types of oil depending on what it was used for (bunker oils vs. diesel or petrol fuel oils), and these oils behave in different ways if released into the ocean.

The focus of Project Tangaroa is wrecks from the two World Wars as they present a particular set of management challenges. PPWs can be safety hazards, and at the same time support local biodiversity. They can have significant heritage value, and many still contain human remains. Some are considered to be war graves. There is a need for policy solutions at national and international levels that both address this complex reality and assure timely action.

While Project Tangaroa is concerned with oil, there are other types of pollutants which can be trapped on shipwrecks. These include unexploded ordnance and munitions, and the toxic and carcinogenic compounds they can leak. The issue of munitions (from dumps as well as shipwrecks) is being covered by the Remediation, Management, Monitoring and Cooperation addressing North Sea UXO (REMARCO) project. Tangaroa and REMARCO cooperate closely and will work together to develop protocols for dealing with the toxic legacy of war.

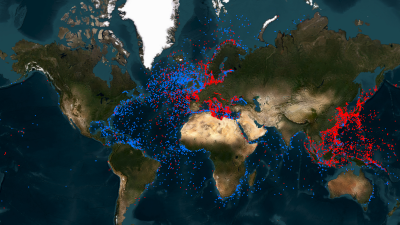

A study in 2005 for the International Oil Spill Conference compiled a worldwide dataset of PPWs, focused on larger vessels such as tankers, and identified 8,569 such wrecks. While this figure is considered to be a robust indicator of the scale of the PPW challenge, the study itself acknowledged that this may be an underestimate, saying: “there is considerable evidence that there is a much larger set of wrecks of smaller vessels that, while holding less oil, could present significant environmental hazards on a localised level. Available data on many of these smaller vessels were excluded from the database due to the parameters of vessel size that were set. At present, this is the most complete data set available. It appears unlikely that the database has failed to capture the vast majority of the largest vessels, particularly tankers, which hold the greatest amount of oil.”

Experts who participated in the three Project Tangaroa workshops endorsed the view that the 8,500 figure is likely to be an underestimate. Other studies have also highlighted the potential importance of smaller, often poorly documented vessels – specifically those under 100 gross tons. These are often excluded from risk assessments due to their perceived limited capacity for polluting materials. However, even small leaks from vessels in shallow water near sensitive sites can have significant impacts. The aggregation of shipwrecks, particularly concentrations of these smaller vessels, may pose a significant regional pollution risk – equivalent to that of a larger vessel. In the UK, for example, areas identified with particularly high concentrations of these smaller vessels include the approaches to the ports of Liverpool, Hull, Great Yarmouth/Lowestoft, and London. Aggregated risk from multiple smaller vessels is also a primary concern for aquaculture sites, especially on the west coast of Scotland.

As well as only being focused on large vessels, the 8,500 figure relies heavily on documentary sources. When it comes to desk-based surveys or risk assessment, many of the wrecks identified as pollutant threats, or considered to be polluting, have not been discovered yet. They have not been surveyed or assessed for how much oil could be trapped within the hull. Some of these wrecks may not actually be a risk, but some may pose far greater risks than expected.

The South-Asian Pacific region has the highest estimated percentage of the known tank vessels and a large percentage of the worldwide estimate of oil remaining. The ‘Blue Pacific’ is also one of the most vulnerable environments when it comes to even small amounts of oil leaking, as the “health of the ocean is fundamental to the sustainability of all aspects of island life”. The second highest region of PPW concentration, when it comes to tank vessels, is also in the Pacific: the northwest. Here, more than 15% of known tank vessels, with 5% of the global oil total, is encased in the fragile hulls of the legacy wrecks.

War wrecks pose growing threats in the Baltic and North Sea regions. The Baltic is a vulnerable inland sea with a low capacity to self-purify and flush pollutants from the system. It saw high volumes of ship traffic during the World Wards, and a mix of merchant and naval wrecks remain, as well as other vessels sunk in storms or collisions. For example, in 1945’s Operation Hannibal alone, roughly 250 vessels sunk, many carrying fuel. In the North Sea, there are thousands of ship and aircraft wrecks, mostly sunk in sea battles during the World Wars or scuttled during post-war dumping activities.

The North Atlantic Ocean has an estimated quarter of the world’s PPWs, with a high volume of oil within them. This is not surprising, given the volume of war activities seen in the region. The German U-boat campaign during the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’, for example, sunk some 3,500 merchant ships alone.

The Mediterranean has a smaller percentage of vessels and oil, but considering its size and fragile environment, the number is concerning. The area saw a large amount of wreckage during the Second World War. The DEEPP (Development of European guidelines for Potentially Polluting shipwrecks) project attempted to record these vessels in one area and found that only a quarter of the wrecks were previously known.

The Arctic Ocean saw millions of tonnes of ship traffic during the First and Second World Wars. In World War Two in particular, Germany’s invasion of Norway and the Soviet Union meant that the Allies needed Arctic convoys to keep these trade routes open. Many ships failed to return from these journeys, as they were targeted by German warships. In the South Atlantic, Allied economic blockades also resulted in many casualties.

A large number of studies have been undertaken on oil spills, such as the Exon Valdez, examining short and long-term impacts. The harm to communities and nature is profound and enduring. Economic and sociological studies have shown that livelihoods are destroyed and both physical and mental wellbeing are damaged.

Psychological stress, including depression and anxiety, affected those reliant on natural resources following the Exxon Valdez oil spill and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The psychological stress can lead to heavy alcohol and drug consumption and increased domestic violence.

There is clear evidence that women have frequently been particularly badly impacted both economically and in terms of safety when collecting food from affected coastal areas. Further, key sources of employment in coastal areas, such as tourism, are hypersensitive to even small oil spills.

PPW impact modelling has been conducted, but issues such as depth of release, hydrodynamics and weather patterns must all be factored in. The specific impacts can also vary depending on the type of oil released (gasoline, crude oil, diesel, heavy fuel oil, etc.) and the environmental conditions when the spill occurs. However, computational spill modelling is advancing rapidly as a management tool to enhance readiness and spill response planning.

When spills from PPWs occur in remote areas, the impacts may be worse and help harder to provide.

Three quarters of the estimated PPWs in the ocean are from World War II and have been underwater for eighty years – those from the First World War over 100 years.

Research on corrosion rates and potential causes of acceleration of those rates suggests that the risk of a catastrophic release is large. Climate change factors such as warming water temperatures, acidification and the increase in hurricanes, typhoons and storm surge only add to the threat of structural collapse and catastrophic release.

Other reasons for concern include observations on how leaks are currently occurring – not through single impacts or a major disturbance event but through a generalised weakening of seams and fastenings that point to decreasing integrity of the hull structure. Increased ocean industrialisation, dredging, mining, and bottom trawling, and new factors like deep sea mining, all become greater risk factors when the hull structures themselves are becoming less robust.

For the vast majority of PPWs we have limited detailed information on their condition. This in itself is a major problem. However, modern survey methods and advanced digital modelling have been applied to a growing number of wrecks, providing an unprecedented level of detail about the structures and rates of change. The evidence from such surveys is consistent and concerning. For example, in the case of the SS Derbent, a World War I tanker, multibeam survey data showed catastrophic collapse over a much shorter time period than previously believed.

It is not always necessary to remove oil from a PPW – in some situations leaks can be controlled and monitored and surface booms used to manage oil that does escape. However, when a decision is made that removal is the best option, highly effective techniques are available that have been developed through decades of experience in the oil and gas sectors. The industry standard intervention is known as ‘hot tapping’. This involves fixing a plate to the hull structure that allows a hole to be drilled through with minimal leakage of oil. A valve system then allows a hose from the surface to be attached, and the oil pumped out. Often, it is necessary to pump steam or heated water into the space containing oil in order to make it flow. Such techniques have been applied successfully to PPWs.

Advances have been made to refine the hot tapping process with better cutting techniques and increased use of remotely operated vehicles to replace divers. However, like many marine engineering operations, it is relatively expensive. Large depths, low temperatures and heavy oils can all add operational complexity and safety risks. Particularly with regard to PPWs, the efficiency and effectiveness of such techniques depends heavily on the quality of the information available to assess oil volumes and plan the work. Ideally, archive drawings and engineering reports can be combined with contemporary high-resolution geospatial surveys in order to optimise operations. However, for many PPWs, there is little information available and even with such input, intrusive methods – which are potentially problematic – are generally used to assess oil location and volume.

It is rarely economically feasible to remove all the oil from a PPW, meaning future leaks remain possible even after hot tapping. Strict rules and regulations also govern the transport and disposal of the oil (which can include resale). In many areas where PPWs are a threat, facilities for safe and sustainable disposal of the oil do not exist locally. This can impose significant cost and complexity, especially if transport across jurisdictional boundaries is required. As PPW hull structures become more fragile and dilapidated, it may become much harder to apply some of these standard techniques to achieve controlled release of residual oil.

To date, several countries have developed their own methods for PPW risk assessment and management. Unsurprisingly, these reflect particular local conditions and administrative priorities.

For example, in the Baltic Sea region, several countries have developed protocols to assess the risk of marine pollution from PPWs. The Swedish VRAKA methodology is recognised by several other states at the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission (HELCOM). The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RULET method is widely referenced as a tested risk-based approach.

The UK E-DBA methodology, commissioned by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) and developed by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), goes through a staged approach focussing on environmental impact. However, the E-DBA is just one of the tools used by the MoD to evaluate and prioritise interventions.

While there are similarities and common reference points between these approaches, such as multistage assessment, there are also marked differences in the weight given to different factors. For example, it has been reported that the Finnish approach has moved away from risk assessment to incorporate detailed consideration of the practicality of oil removal in each case.

The actions needed to prevent pollution from PPWs should be effective and prioritised by the relative risk to the environment, and the lives and livelihoods dependent upon a healthy ocean and coast. International standards based on the current best practices are therefore important for facilitating socio-economic, environmental and heritage goals in a sustainable manner. This includes classifying PPWs and their associated risks according to potential environmental, social, and economic impacts.

As the next steps require cooperation of states at the international and local level, having these standards, guidelines or a toolkit on the various steps will help governments and other stakeholders know how, where and when to act, and allocate global resources most effectively.

There are many domestic and international mechanisms that are designed to deal with oil pollution. Generally, they are for reacting to recent spills from privately owned oil tankers, as opposed to a preventative or precautionary approach to address threats from legacy wrecks such as those from the World Wars.

A number of international conventions adopted at the IMO since 1969 have imposed liability for oil spills on shipowners and their insurers, as well as establishing the IOPC Fund – this fund contributes to covering liability for spills from tankers, and is paid for by tanker cargo interests in each contracting state.

Similarly, the IMO Wreck Removal Convention sets out a clear international framework of obligations, roles, responsibilities and liabilities for the removal of hazardous wrecks. However, all these conventions (and the IOPC Fund) only impose obligations and liabilities for spills that have occurred after these conventions came into force. They do not apply retrospectively and therefore cannot impose liability for events that occurred during the World Wars. Moreover, these conventions apply to private entities and not necessarily to wrecks of state-owned ships.

This and other factors mean PPWs are generally underrepresented in national and regional oil spill contingency planning. They are also not routinely included in risk assessments and due diligence in advance of Blue Investments and habitat restoration programmes.

Major operational challenges also exist, and it is important to note that PPW spills would further stress already thinly-spread provision for major spill response. If a problem occurs in connection with a planned oil and gas exploration or production campaign, there is rapid access to a mature infrastructure such as shore bases and on-water assets (platform supply vessels, anchor handlers and crew vessels). There will also be a containerised offshore response package made up of 3x10ft containers containing offshore booms, power packs, skimmers, temporary storage, dispersant and a delivery system. The ships’ crews will have received regular training on the deployment of these systems, and benefit from a multi-million-pound level of investment. When responding to a PPW leak however, these valuable and essential assets are not available at short notice and in the majority of circumstances negotiation would be required to establish who will fund acquisition of them.

In terms of overall provision for spill response, existing equipment stockpiles are very few and far between and certainly not available in remote areas (such as the Arctic and the Pacific Islands). Those that are in place are likely to be pre-committed, as with the Maritime and Coastguard Agency stockpile in the UK.

As matters stand, a large-scale spill from a PPW is likely to occur with no prepositioned equipment or agreements in place. The severity of the outcome is therefore inevitable. Even if equipment resources were available, pre-agreed arrangements would have to be in place to allow their deployment, and training of a local workforce would be required to assure occupational safety, maintenance, and rehabilitation.

Under international law, as reflected in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC), all nations have a duty to protect our cultural heritage and the natural heritage or marine environment.

However, many PPWs from World War II sank off the coasts of nations that were not even sovereign states during that war, such as the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Solomon Islands.

Most of the flag states involved in World War II have stated that unless expressly abandoned, the wrecks of their sunken state vessels continue to be owned by them and are therefore subject to sovereign immunity. Moreover, the sovereign immunity asserted here is also found in the LOSC – including provisions regarding protection of the marine environment – and other international laws such as the 2007 IMO International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks (also known as the Nairobi Wreck Removal Convention).

This arguably implies that flag states claiming property title over such sunken state vessels not only remain the owners of such property, but also have a duty or responsibility to other nations regarding the possible threats to the marine environment they pose. Article 31 of LOSC stipulates that the flag state “shall bear international responsibility for any loss or damage to the coastal state resulting from the non-compliance by a warship […] with the laws and regulations of the coastal state concerning passage through the territorial sea or with the provisions of UNCLOS or other rules of international law”.

While flag state’s PPWs may be immune from arrest, flag states including the US and Japan have cooperated with coastal states on a case by case-by-case basis in the past, to address the threat to the marine environment. They will hopefully be willing to cooperate in the future in a way that avoids or minimises pollution and adverse impacts to cultural heritage.

Privately owned tankers and vessels that have been chartered by the flag state in support of their efforts in war may also be subject to sovereign immunity if not on commercial service.

There remains a major deficit in resources committed to PPW management and there is no uniform implementation of a precautionary approach. However, it is not true to say that flag states have been inactive – as demonstrated by the examples below.

Funded by the US Congress, NOAA conducted a desktop inventory and risk assessment for PPWs in the US Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). This included the development of the Risk Assessment Report and RULET database for use by the US Coast Guard, the lead agency addressing oil spills in the US. However, it was completed more than a decade ago, and Congress has not provided additional funding to take the next steps necessary for a preventative or precautionary approach that would avoid or minimise a catastrophic release.

The US Navy has taken a case-by-case approach to its PPWs in foreign waters, but there is no funding or planning for a desktop risk assessment study, much less plans for emergency response or long-term plans for cooperation with foreign nations with US PPWs in their waters. The management of PPWs is thus split between the Coast Guard, the Navy and NOAA.

Management of UK Government wrecks is split between the MoD and the Department for Transport. The environmental risk posed by the MoD’s inventory of PPWs – comprising approximately 5,700 wrecks around the world, dating from 1870 onwards – is managed by Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S) Salvage and Marine Operations (SALMO). The SALMO Wreck Management team manage this risk on behalf of Navy Command. Wrecks as historical entities are managed by a separate team in Navy Command.

Proactive management of MoD PPWs can be traced to February 1995, when the then-Secretary of State for Defence accepted that the UK MoD had a moral responsibility to intervene on HMS Royal Oak, which had recently started to leak significant amounts of oil into Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. This eventually resulted in the MoD taking management responsibility for its wider inventory of PPWs. The MoD policy on wrecks is laid out in JSP 418 Leaflet 10.

Japan, like the US, has undertaken some case-by-case cooperation, such as in the Solomon Islands. However, there appears to be no inventory or risk assessment, much less contingency or long-term planning to avoid or minimise the threat of pollution or harm. Japan has provided funding for a program regarding recovery of human remains that may be helpful in addressing the threats from Japanese PPWs that also contain them.

Germany was actively involved in the North Sea Wrecks (NSW) project between 2018 and 2023, which spurred the subsequent REMARCO project. NSW involved cooperation between research organisations in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and Norway, with each country investigating several wrecks within their territorial waters and/or EEZs. The focus was (as with REMARCO) on munitions still onboard the sunken wrecks and their possible impact on the marine environment.

While emergency response operations for PPWs have occurred, they “serve to highlight the need for a more proactive approach in the future, where PPWs can be assessed, and the risks identified in a planned campaign”. A strategic, coordinated, approach is needed and will reduce the pollution risk and impact on ocean communities. If no proactive approach is taken, the estimated costs for the potential pollution response and clean-up is in the billions of dollars, plus the immeasurable environmental, economic, and human impacts.

In June 2025, Project Tangaroa published the Malta Manifesto, which contained key calls to action to address the threat of potentially polluting wrecks. Now, this new in-depth report underpins the Manifesto, with insights from across the coalition.

Read the report